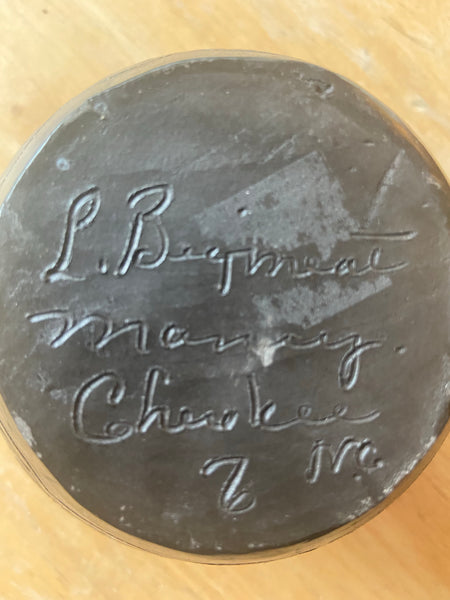

Vintage Collector's 4” Pottery Bowl by Louise Bigmeat Maney

3”h x 4”w

“I was about six or seven when I started doing pottery,” Louise Bigmeat Maney said. “When I was a girl growing up, we used to dig our own clay up here near the Macedonia church on the creek bank.” She recalled that her older brother “had a sled and a steer, and he’d haul the clay home. And then we’d lay it out on the ground and spread it out and let it dry.” After cleaning the clay, they used an old meat grinder to grind it up.

“We had a big old stove that we cooked on, and we also used it to fire the pottery in.” The family also had a kiln. “It was just a hole in the ground with the sand around it,” she said. The old Cherokee pots had a variety of practical uses, but “time changes and so did the pottery.”

Louise’s mother, Charlotte Welch Bigmeat, and aunt Maude Welch were both prominent Cherokee potters. But Louise traced her pottery lineage back to Ewi Katalsta, the last conservator of pottery among the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians by the turn of the century. Bigmeat pottery is known for its black, shiny finish, achieved through several stages of polishing and firing with soft woods.

While raising a family of eight with her husband John Henry Maney and later teaching in the Cherokee schools, Louise had little time for making pottery. Learning to turn pots on a potter’s wheel in the late 1970s spurred her return to pottery making. Through her designs and techniques she maintained other traditional processes. She used the same tools her mother used: deer bone knives and stones for polishing; and peach seeds, corn cobs, and wooden paddles for applying designs. With a sharp stick, she incised traditional patterns that resemble those used in Cherokee weaving and basketry.

In 1990, Louise and John Henry opened the Bigmeat House of Pottery in Cherokee. Her commitment to preservation spurred interest among other tribal members as well as visitors to her shop. Louise felt that many of the tribe’s young people would return to craftmaking—much as she did—in later years. For Louise Maney, innovation was part of the process of preserving tradition. She received the North Carolina Heritage Award in 1998.